AWeb site features a lurid photograph of one fist clenching a pair of balls and the other brandishing a machete. Those who have braved such sites know that castration is one of the most extreme forms of body modification -- hacking off your testicles is certainly more permanent and life-changing than mere brands or tattoos. Some men fantasize about castration, but only a handful actually do it. A few even try it at home -- and often end up in the emergency ward.

The aforementioned Web site, Eunuch.org, gives castration rare public exposure. These days, it has gone underground in the Western world. You rarely hear about the removal of human testes, except perhaps in male-to-female sex changes, certain cancers, religious cults, and the edgiest S/M or B&D play. Yet castration has been around as long as there have been balls to cut off. Ancient Persians used it to torture enemies, the Greeks and Romans to domesticate slaves. The Muslims cut off both the balls and penises of the men who guarded the sultan's harem.

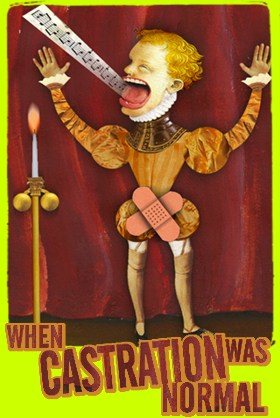

But castration wasn't always intended to be unkindest cut. Three hundred years ago, castrati captivated the Western world the same way androgynous rock stars David Bowie and Marilyn Manson do now. Indeed, castrati inspired frenzied adoration in their fans, who wore medallions emblazoned with pictures of their favorite castrati singers.

The word "castration" comes from the ancient Sanskrit "sastrum," or "knife." But this practice reached its zenith in the West during the Baroque period (17th and 18th centuries), when the Italian castrati ruled the European operatic stage. In The World of the Castrati, Patrick Barbier explains that castrati were ubiquitous in the Baroque opera. To produce a castrato, a boy's testicles would be removed before his voice broke (ideally between the ages of eight and 10). If he was among the lucky 20 percent who survived this process, he was shipped off to a conservatory, where he endured years of severe vocal training for the slim chance of becoming a great singer. This training -- and along with it the castrati -- vanished for the most part after the Baroque era. As a result, we have little idea how they sounded, and there are only a few recordings from 1902 -- the year when castrati were finally banned from the Sistine Chapel choir. Alessandro Moreschi, the "last castrato of the Western world," is no great singer, but his voice -- a childlike soprano with a man's projection -- is like nothing else on earth.

Since there are no memoirs of castrati, we have no idea how many remembered being castrated. Most doctors pressed their little patients' carotid arteries until they passed out before making the cut. But some castrati resented their families for cutting their balls off without consent. Domenico Mustafà, whose family told him that a pig had eaten his balls, swore he'd kill his father if he discovered he'd authorized the procedure. And when Loreto Vittori's father asked him for money, the singer replied that all he owed his family was an empty purse, or "bourse," which also means "scrotum."

Castrati were indeed different from other men. A lack of testosterone prevented the development of male secondary sex characteristics and increased the production of female hormones. As a result, the adult castrato had a feminine body and retained the high-pitched voice, hairlessness, and small penis of a child. Since testosterone also counteracts the production of growth hormone, some castrati reached extreme height. In general, the castrati had low sex drives, but not always. Most castrati could become erect and ejaculate, but their come consisted solely of prostate fluid with no sperm. For this reason, the Church, which condoned sex for procreation alone, frowned upon sexually active castrati. Despite this, many castrati were famous for their exploits with noblewomen. Pregnancy was scandal, and castrati were a convenient method of birth control.

The castrati's unique sexual features inevitably led to a very seductive sort of gender confusion. Cut singers played the roles of both men and women on stage. At the start of the 18th century, when papal edict forbade women to act or sing, many castrati dressed as women, and women disguised themselves as castrati to enter the forbidden world of the theater. While the Church railed against cross-dressing as a cause of sodomy, castrati were courted and kept by priests and cardinals, who perhaps found it easier to tolerate their desires for men in the guise of women. Weirdly enough, Casanova fell in love with a castrato who turned out to be a woman disguised as a castrato. But he was so enamored with her male persona that he asked her to dress in disguise before they made love.

The castrati may seem like contemporary cross-dressers. Perhaps that is the closest we can come to understanding the roles they played in their culture. But in a sense, it is a mistake to use the terms "cross-dressing," "transgender," or "androgynous" -- as well as "homosexual" or "heterosexual" -- with respect to the castrati. These are our terms for contemporary concepts, and they are as distant from the castrati as the boys singing in the conservatories are from the eunuch Web sites.

Castrati were worshipped by their societies, but were also taken for granted: They were so much a part of their culture that none of their contemporaries thought to study them as an extraordinary phenomenon. The castrati embodied the Italian Baroque, which thrived on artifice and disguise. They vanished into history, and their voices vanished with them.

Lisa Montanarelli is a freelance writer and independent scholar in San Francisco.